Why can’t this be done in an academic lab?

Academic expectations (publishing, grant acquisition, teaching) often prevent large-scale, team projects with high engineering scope from taking shape. Further, recruiting top talent for low-paying, short-term post-doctoral positions is extremely challenging. Also, this work sits between basic and applied science, making it difficult to fund. Targeting hundreds of disordered biomolecules and obtaining mechanistic insight for these interactions is generally not possible in academic settings. For these reasons, an FRO is the ideal (and probably the only viable) structure for this project.

Why won’t VC/large pharmaceutical companies do this?

We will create a large, publicly-available dataset for the benefit of the UK R&D ecosystem. Pharmaceutical companies and start-ups are disincentivised from sharing their tools, hits, and understanding of general binding mechanisms, even though doing so could dramatically accelerate drug discovery and improve societal health.

Why can’t you just dock to AlphaFold structures?

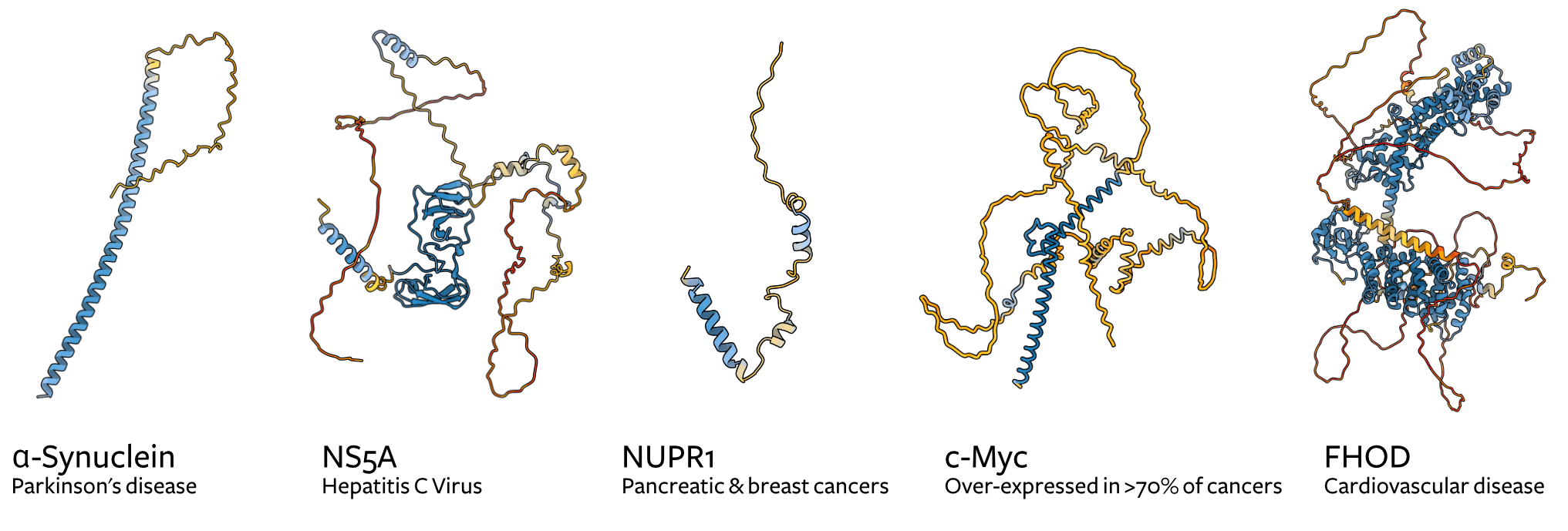

AlphaFold2 and AlphaFold3 were trained on the Protein Data Bank, a database of protein structures. Many protein structures in this database either do not have disordered regions (they were removed for X-ray crystallisation) or could not be resolved (e.g., in cryo-EM structures) due to their highly dynamic nature. AlphaFold2 confidence scores are a good predictor of whether a given region is disordered (low scores correlate with disorder), but it cannot give us much more information beyond this, particularly in the context of small-molecule interactions (Figure 1).

How will small molecules get inside cells?

While some disordered proteins are extracellular, several function intracellularly. We will employ various strategies to ensure that therapeutics can enter cells including experimental and computational optimisation of lipophilicity to ensure that small molecules can passively diffuse across the cell membranes. Furthermore, we will also explore pro-drug, carrier-mediated transport, and nanoparticle-based drug delivery strategies.

Are disordered proteins really disordered in cells?

Yes, recent experimental work has demonstrated that while the cellular environment can tune structural ensembles of disordered proteins, disordered proteins’ lack of secondary structure persists in the cell (Moses et al., Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol., 2024, Theillet et al., Nature, 2016).

Can we learn more about and improve existing therapeutics?

A highly general platform designed to screen for small molecule binders of disordered proteins could significantly enhance our understanding of the side effects and toxicity associated with existing drugs. By mapping the interactions between small molecules and a wide array of disordered proteins, we can identify off-target effects that contribute to adverse reactions, thereby illuminating the complex network interactions within biological systems. Such comprehensive profiling would facilitate a more holistic approach to drug safety assessment, enabling the prediction and mitigation of side effects through an integrated view of drug action and cellular response pathways.

Can we help find new treatments for cancer?

Intrinsic protein disorder is prevalent in cancer, with many oncogenic proteins exhibiting disordered regions that facilitate complex signalling and regulatory mechanisms. This intrinsic disorder in proteins often contributes to the molecular heterogeneity and adaptability of cancer cells, making them more resilient to treatments. Bind will have a strong focus on disordered proteins involved in various cancers, for a detailed list see the appendix.

Can we learn more about fundamental biology?

Small-molecule interactions with proteins underpin vital processes across biology. Approximately one-third of all eukaryotic proteins contain some degree of disorder, and early evidence suggests that these regions can indeed interact with small molecules. Nevertheless, there is currently a major technological gap, as we lack methodologies for biomolecular characterisation of the elusive interactions between disordered proteins and small molecules. Bind will develop cutting-edge biophysical methods to allow scientists to probe these highly dynamic interactions. For example, this work will allow us to uncover basic mechanisms of how metabolites and other small molecules interact with and alter the structures, functions, and stabilities of disordered proteins.

Why will we be protecting IP?

For a pharmaceutical company to develop a drug at a cost of potentially hundreds of millions of dollars, it needs assurances that it can recover this cost over some time frame after drug approval. This happens through patent protection, and allows the company to have a limited-time monopoly on the production and sale of a certain drug. Due to the relative ease of manufacturing a drug compared to research and development of it, not having a patenting system like this in place would disincentivise industry from developing new medicines. To ensure our findings can emerge into novel drugs, we thus need to protect our small-molecule hits and exclusively license this information to ensure maximum translational impact. As a non-profit organisation, any revenue generated by Bind will be re-invested into Bind to help the organisation achieve its mission.