The lock-and-key binding paradigm for folded proteins

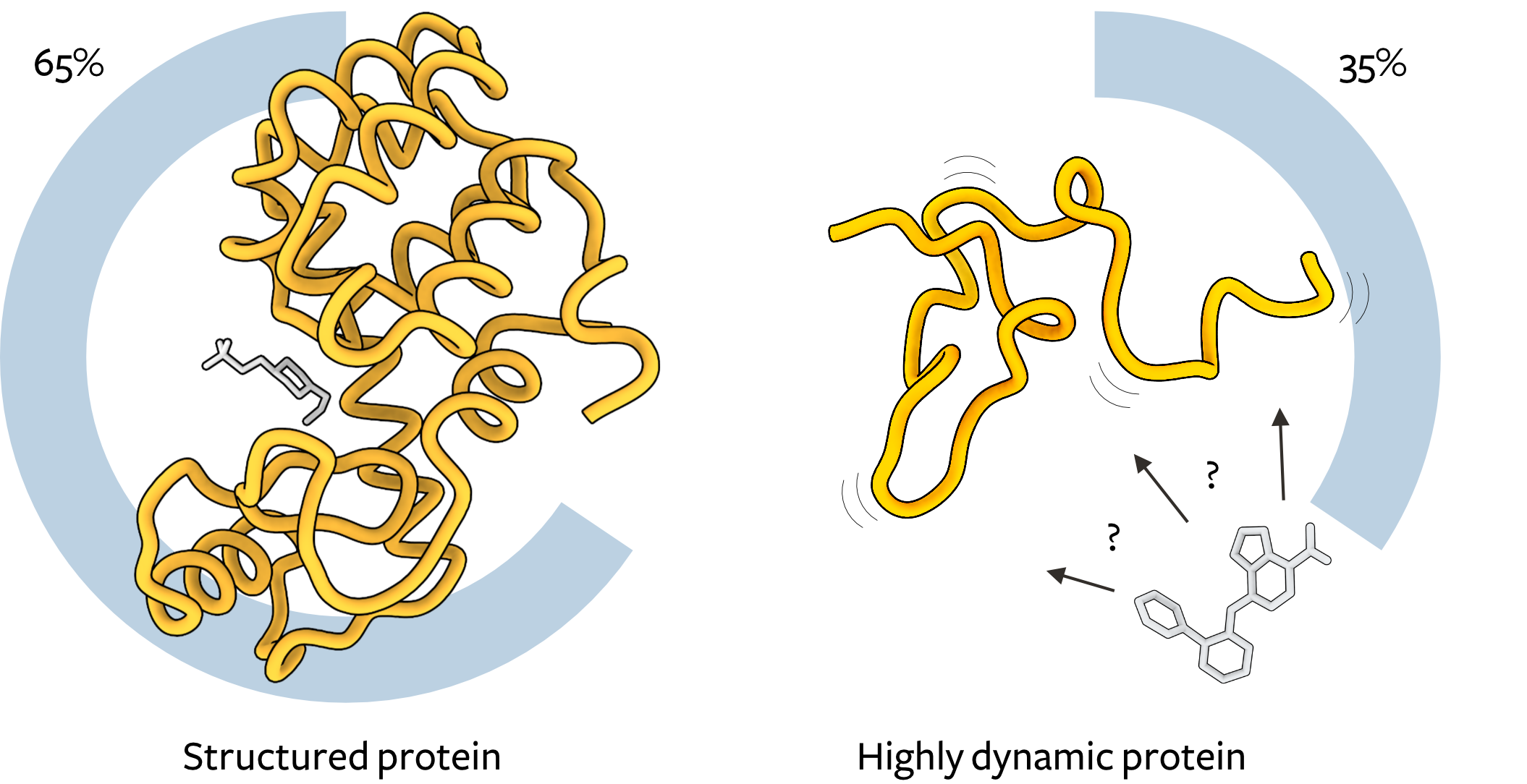

Small-molecule interactions with proteins are ubiquitous in biology, underpinning signalling, metabolism, and therapeutic intervention. Despite the importance of such interactions, our current understanding is limited to interactions between small molecules and structured proteins (Figure 1, left), whereby small ligands (grey) are often simply described as fitting snugly into well-defined binding pockets, like a key fitting into a lock (thus termed ‘lock-and-key’ binding). While there are extensions of ‘lock-and-key’ binding (e.g., induced fit), most drug discovery today relies on the presence of long-lived binding pockets on protein surfaces.

Unlocking new paradigms for dynamic biomolecules

Many proteins lack such long-lived binding sites for small molecules. The most extreme example of such proteins are disordered proteins, biomolecules which are highly dynamic, rapidly interconverting between different shapes, and are abundant in eukaryotes (Figure 1, right). Disordered proteins are highly prevalent, making up one-third of the human proteome, and play major roles in cancer, cardiovascular disease, neurodegeneration, and viral infection. Despite this, due to their highly dynamic nature and lack of long-lived binding pockets, disordered proteins have generally been considered to be ‘undruggable’. Nevertheless, researchers have demonstrated that disordered proteins can indeed bind small molecules and discovered new interaction mechanisms. These mechanisms differ dramatically from ‘lock-and-key’ binding. Both the small molecule and the disordered protein remain extremely dynamic in the bound states.

State-of-the-art drug discovery

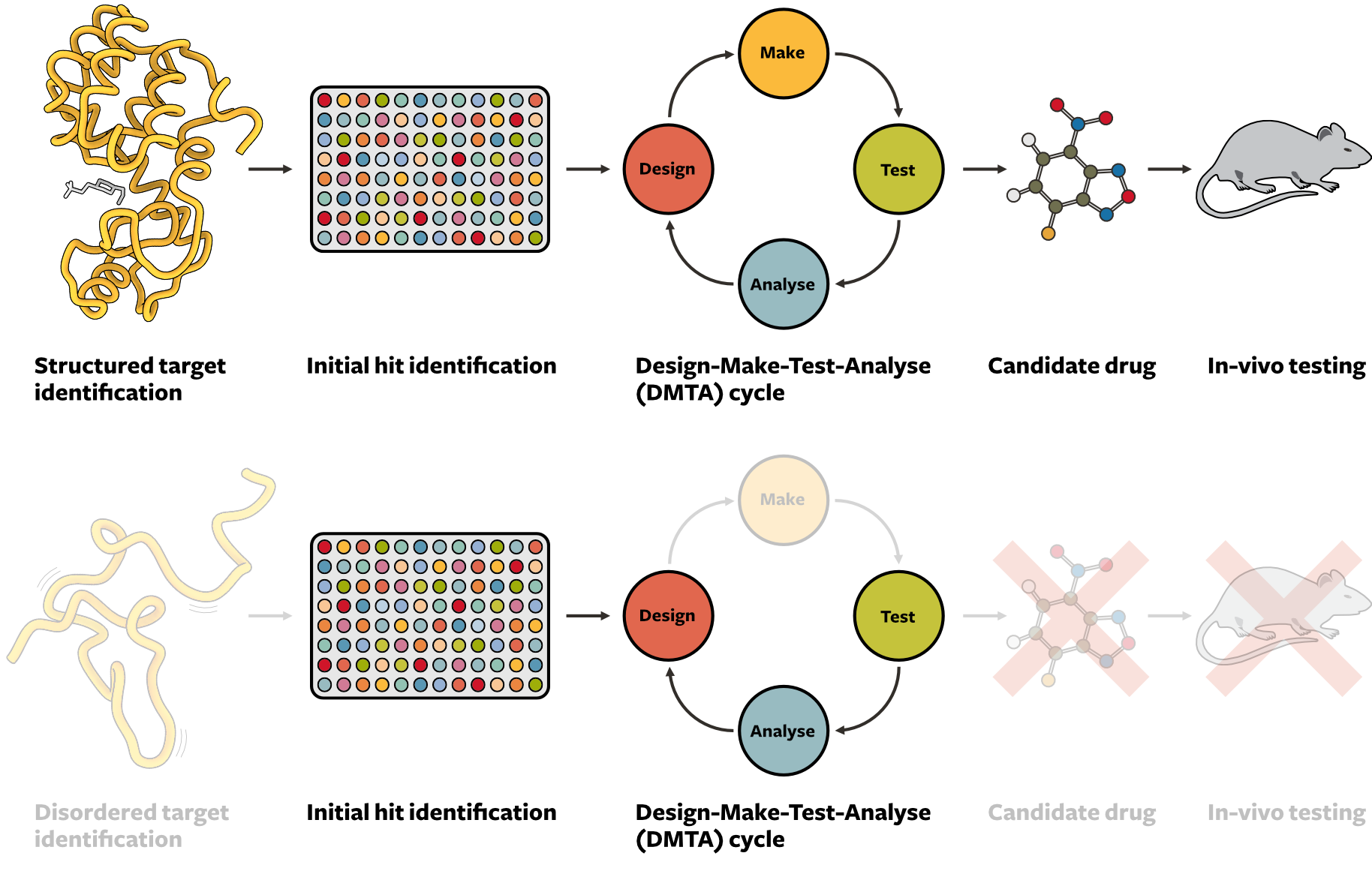

For folded proteins, there are a battery of computational and experimental approaches to discover new drugs, which have been highly optimised. For example, docking is a computational approach in which small molecules are geometrically fit into a static protein binding pocket and then scored based on their interactions. Experimentally, X-ray crystallography can reveal the key interactions of a small molecule with a static target in atomistic detail, and allows potential hits to quickly be developed into pharmaceuticals. Most small-molecules that have been identified to interact with disordered proteins and highly dynamic biomolecules have been identified by chance through protein-specific functional assays. However, these approaches require extensive a priori knowledge of the target and its exact function, which is difficult for disordered proteins that are multi-functional and can have hundreds of binding partners. Industrial drug discovery programs typically follow a cycle as depicted in Figure 2 (top). An initial hit for a target is iteratively refined in a design-make-test-analyse (DMTA) cycle before it can become a drug candidate. This process has become highly efficient in recent years due to improvements in computational methods for design, better synthesis procedures, and more advanced testing techniques.

Why now?

Both the design and test stages have been traditionally optimised for folded (i.e. static) proteins, and are mostly unsuitable for dynamic biomolecules (Figure 2, bottom). This is due to a lack of tools available to study and analyse the interactions of small molecules with disordered proteins, both experimentally and computationally. Developing these tools and building computational models is in turn hindered by the lack of datasets describing these interactions. At Bind, we will focus on three areas to make drug discovery for dynamic biomolecules possible: experimental biophysics, computation, and artificial intelligence.